Elevating compliance data: fighting data fiction and putting purpose at the heart of metric design

The IC MasterClass team

1 June 2024

Data is a critical part of a firm's compliance and risk management story. Metrics give integrity to a strategy, and underpin a firm's reputation for transparency, oversight and accountability. Data both aids a firm in managing risk and being seen to manage it: regulators demand compliance metrics from boards and senior managers to demonstrate competency and taking reasonable steps, and a good dashboard is always in vogue.

Too often, however, a desire for data overtakes perspective, especially in the face of growing stakeholder or regulatory pressure. Measuring what is easy is not the same as measuring what is right, and data without context is a dangerous thing. Incomplete, lagging or biased compliance metrics do more damage than having no data at all: they undermine strategy and culture, and indicate to a regulator that a firm is at best careless, and at worst wilfully blind.

To avoid this trap, a firm needs to have a robust compliance data management system with a core purpose. Its strategy must navigate particular challenges with data quality, ownership, controls and bias. Its purpose must be anchored in the different needs of its audience, including regulators, the board, clients, suppliers and risk oversight functions.

We explain below why purpose must be at the heart of a firm’s compliance data story and consolidate key principles in our signature MasterClass Cheatsheet.

If you want to integrate this MasterClass into your practices, elevate your compliance data strategy or reengineer your risk management metrics, give us a call on 020 7411 9602 or email us.

[Ten minute read]

“It is a capital mistake to theorise before one has data.”

~ Sherlock Holmes, “A study in Scarlet” by Arthur Conan Doyle

1. Why compliance data matters

When data is trusted it underpins decisions, justifies behaviours, and tells compelling stories. Like with any information, if compliance data is given the right platform it will explain, inform, or persuade: it serves a critical purpose in informing risk decisions, demonstrating a firm’s compliance culture, and defending against regulatory scrutiny.

Data is not, however, always credible: it can be subjected, consciously or unconsciously, to bias, stripped of context, prone to human error or otherwise reported in a way that subverts rational decision-making. Data that shows an unwelcome problem can be sanitised or downplayed: if a firm does not want hard truths, it can edit them out.

Whether through a lack of probity, rigour or integrity, through negligence or wilfulness, poor data and misleading reporting will undermine the firm’s compliance culture and ultimately, its reputation when such errors are finally uncovered.

When a regulator no longer has faith in the quality or reliability of a firm’s data and reporting, enforcement is a likely outcome (see the 2020 OCC and FRB $400mn fine against Citibank for data and governance failures, the FCA’s 2017 £163mn fine against Deutsche Bank for AML governance failings, including weaknesses in trading data resulting in mirror trading going unnoticed, and the 2023 PRA £5.4mn fine against Metro Bank for regulatory reporting failures). Data and reporting is vital to a board’s ability to govern its firm, and without it, regulators will question the strength of a firm’s broader governance and control environment.

2. Why firms get compliance data wrong

There is no such thing as perfect data. Over time, good quality data will degrade and data gaps will emerge, and compliance data is no different. Within this limit is a spectrum of robust and poor practices, wilful and negligent, that can lead to egregious mistakes and data corruption. For example:

- Data can be vulnerable to deliberate manipulation and concealment if data analytics teams are not independent and there is no culture of transparency. Reports can be buried if leaders lack conviction to confront difficult realities. This fraudulent behaviour is myopic: born from reward cultures that prioritise short term performance at the expense of sustainability. It can also arise from weak control environments that enable unconscious biases, including groupthink and confirmation bias, to effect data management.

- Desire and good intentions are not enough to ensure that data is fit for purpose: they must be supported by a coherent compliance data system that adheres to core data governance principles (see section 6).

- Data cannot be fit for purpose if no effort has been made to understand purpose (see section 3). Failure to establish compliance data needs at outset creates a myriad of operational and philosophical problems: it can lead to over-reporting that distracts executives from important conclusions, costly and unnecessary data collection, and a distorted compliance picture.

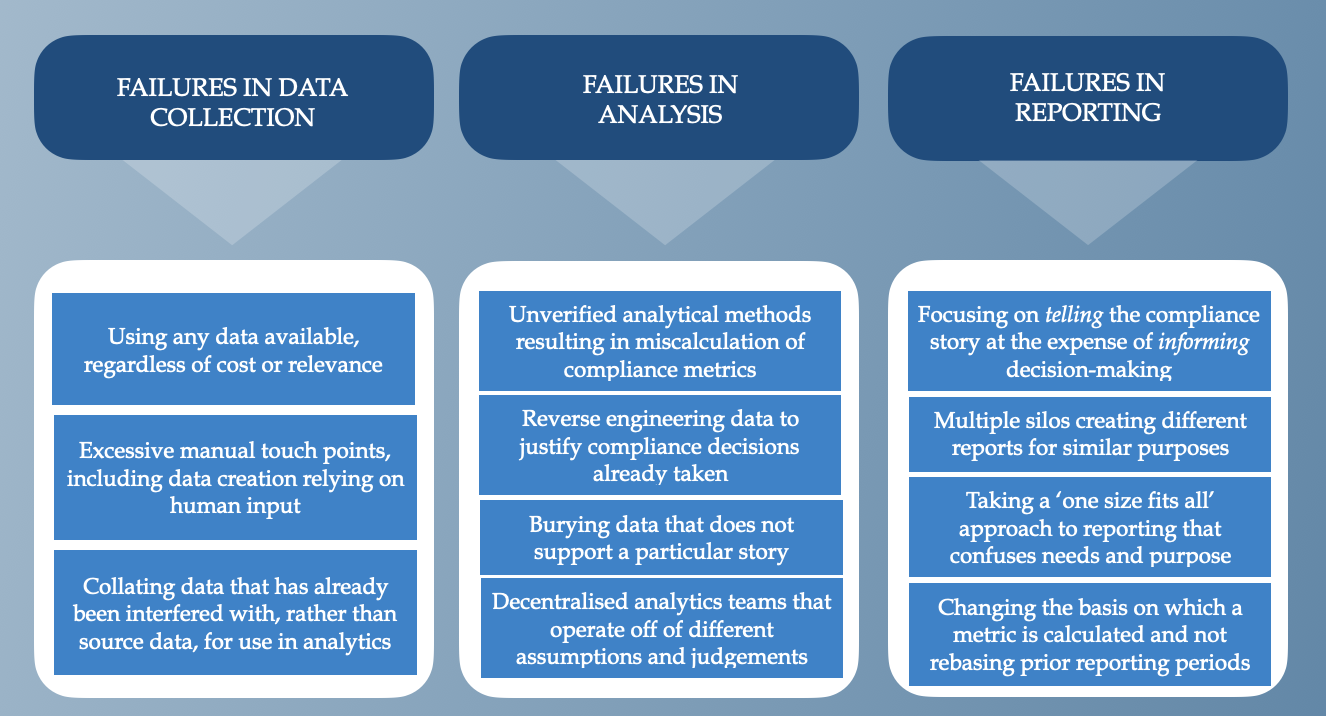

Data failures can be numerous and subtle, and can occur at all stages in the data lifecyle. Data collection failures are often error-based, analytics failures may result from unconscious bias or coercion, and reporting failures can occur due to organisational structures and outside pressures. Common failures include:

Figure one: common compliance data failures

3. Putting compliance purpose at the heart of data design

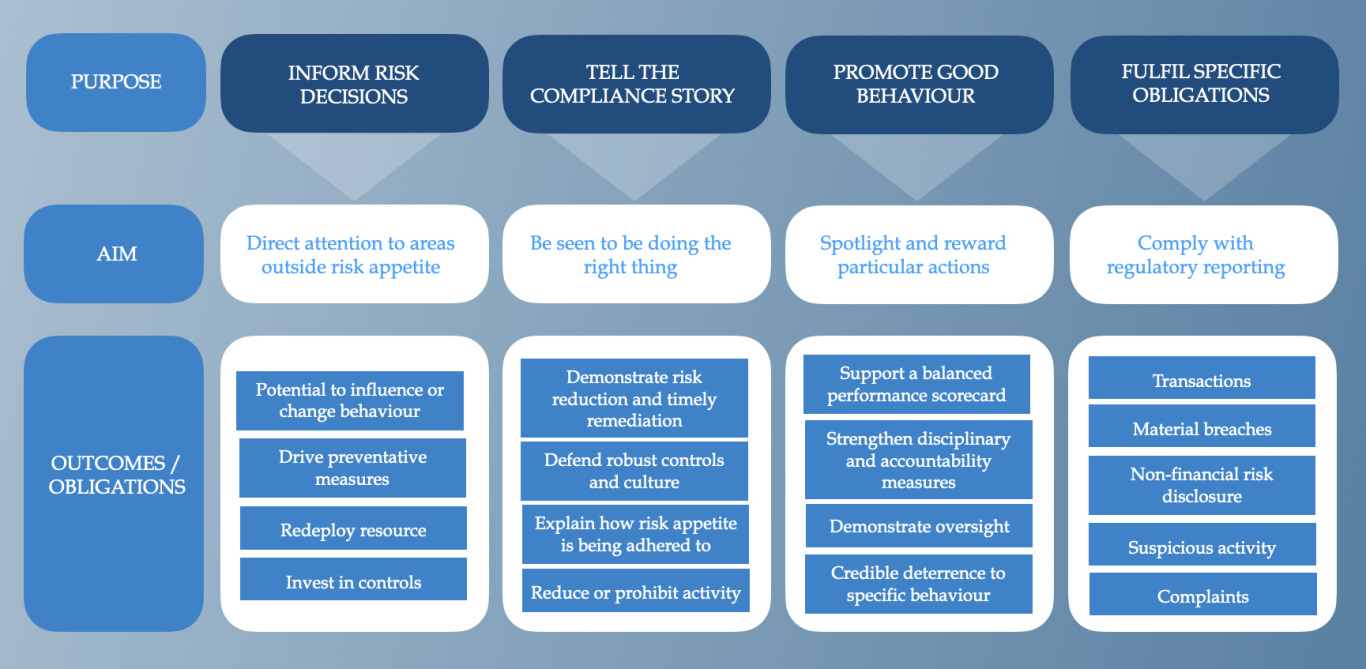

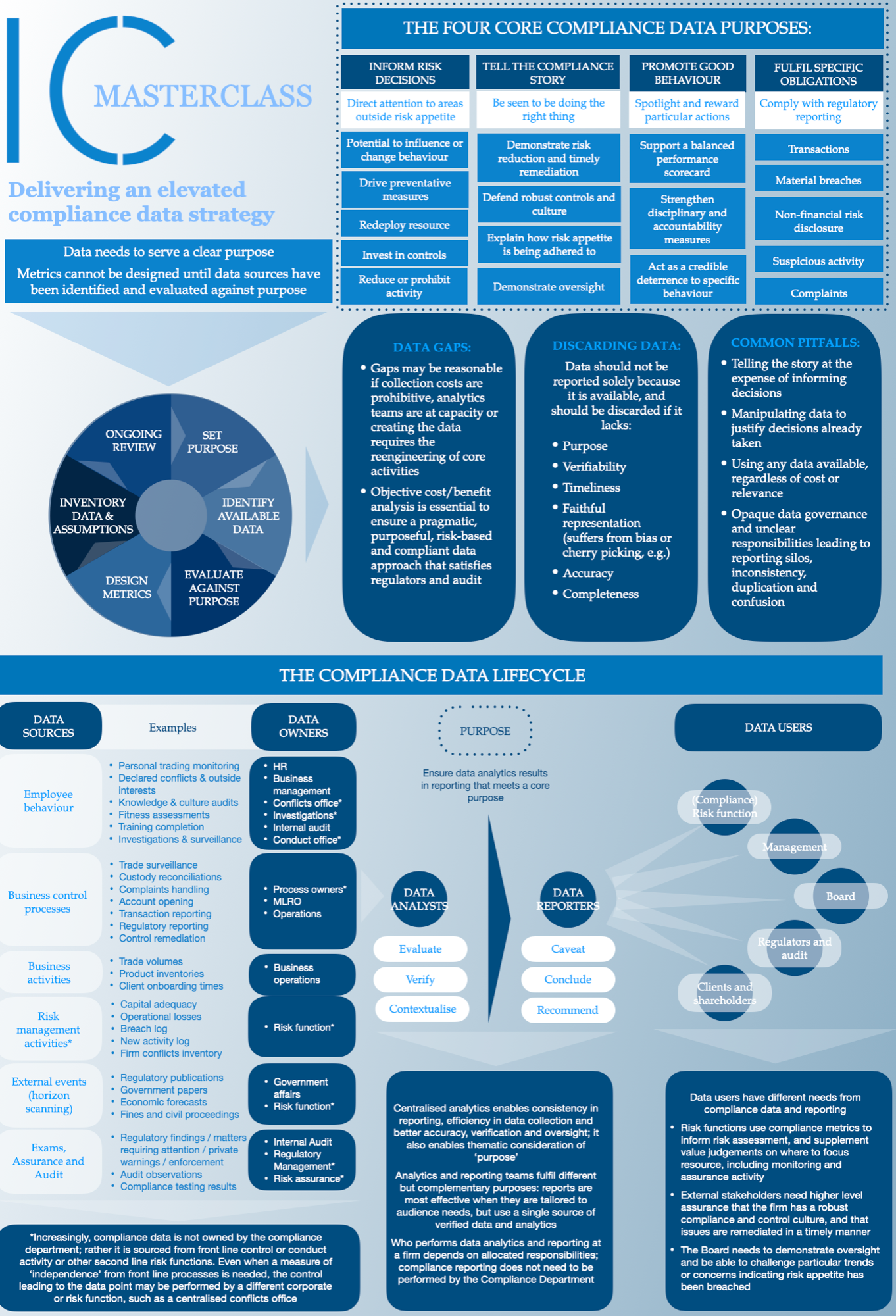

By starting with purpose, a firm can work backwards to ascertain what data to look for and avoid many of these failures. Compliance data serves four broad purposes:

- To inform risk decisions: data should be used to direct attention and resources towards areas of increasing risk, and specifically areas where risk is outside of the board's appetite. Compliance data is purposeful if it can be used to influence or change behaviour (or activity, or process)

- To tell the compliance story: a firm must both do the right thing and be seen to be doing so. It needs to be able to demonstrate that it is reducing risk when its behaviour comes under scrutiny, and demonstrate it has the systems, controls and resources to identify and remediate issues diligently and efficiently. This includes demonstrating the operating performance of the Compliance Department and other teams performing essential compliance-impacted roles (for example, deal conflict clearance or client onboarding). Done correctly, compliance data is an essential part of how a board demonstrates oversight, reasonableness, culture and accountability

- To promote good behaviour: a spotlight on certain data can deter adverse behaviour; individuals behave differently - although not necessarily better - when they believe they are being watched

- To fulfil specific regulatory obligations: black letter rules require the measurement and reporting of specific data internally and to regulators, for example complaints, suspicious activity and transaction reporting

Figure two: core compliance purposes served by data

4. Where to look for compliance data

Compliance data is, increasingly, not owned by the Compliance Department. Compliance data can be sourced from ‘acts of compliance’ (an act expressly required by or to comply with regulation) or ‘acts indicative of compliance culture’ (an act that, whilst not regulated in itself, demonstrates the firm’s broader compliance and control environment).

Many such processes and behaviours are performed or overseen by the front office or operations teams, or by other centralised corporate or risk functions, including a centralised conflicts office, regulatory engagement teams, internal audit, operational risk, middle and back office functions, and business risk management.

Figure three: sources of compliance data

When to select and when to discard data

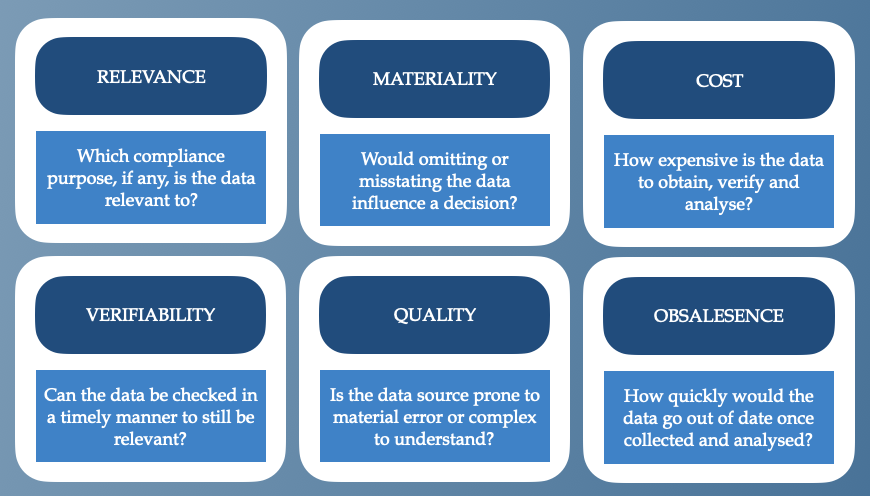

Selecting data is not purely about whether it serves a compliance purpose, but also about its cost-benefit. All data collection and analysis has a cost, and this may be prohibitive.

The more credible a firm’s data management system, the more latitude a firm has to push back against calls, internally from audit or risk functions, or externally from regulators and clients, for unnecessary data or reporting that is not purposeful.

Part of this system needs to focus on robust, and documented, evaluation of the cost-benefit of a particular data point, including the following factors:

Figure four: factors to consider in data cost-benefit analysis

Courage to accept data gaps

Data gaps may be caused by processes, often manual, that do not currently generate data in a systematic way, or because the data conceptually does not yet exist. They may be specific to a firm’s operations, or stem from limitations in industry practices.

Data gaps may not need addressing if the cost-benefit analysis does not support doing so, but a firm must have a justification for its approach.

Accepting a data gap needs to be done thoughtfully and with due regard to how a regulator may view the integrity of the firm’s overall data management system. Certain data is necessary irrespective of its cost (for example, complaints handling data) and failing to invest in data will have long term consequences.

Proactively engaging with regulators to ascertain what data is feasible, and reasonable, for a firm to collect will help a regulator understand where its expectations may be out of alignment with industry realities, especially if there is a push for new regulation in a big data area, such as transaction monitoring.

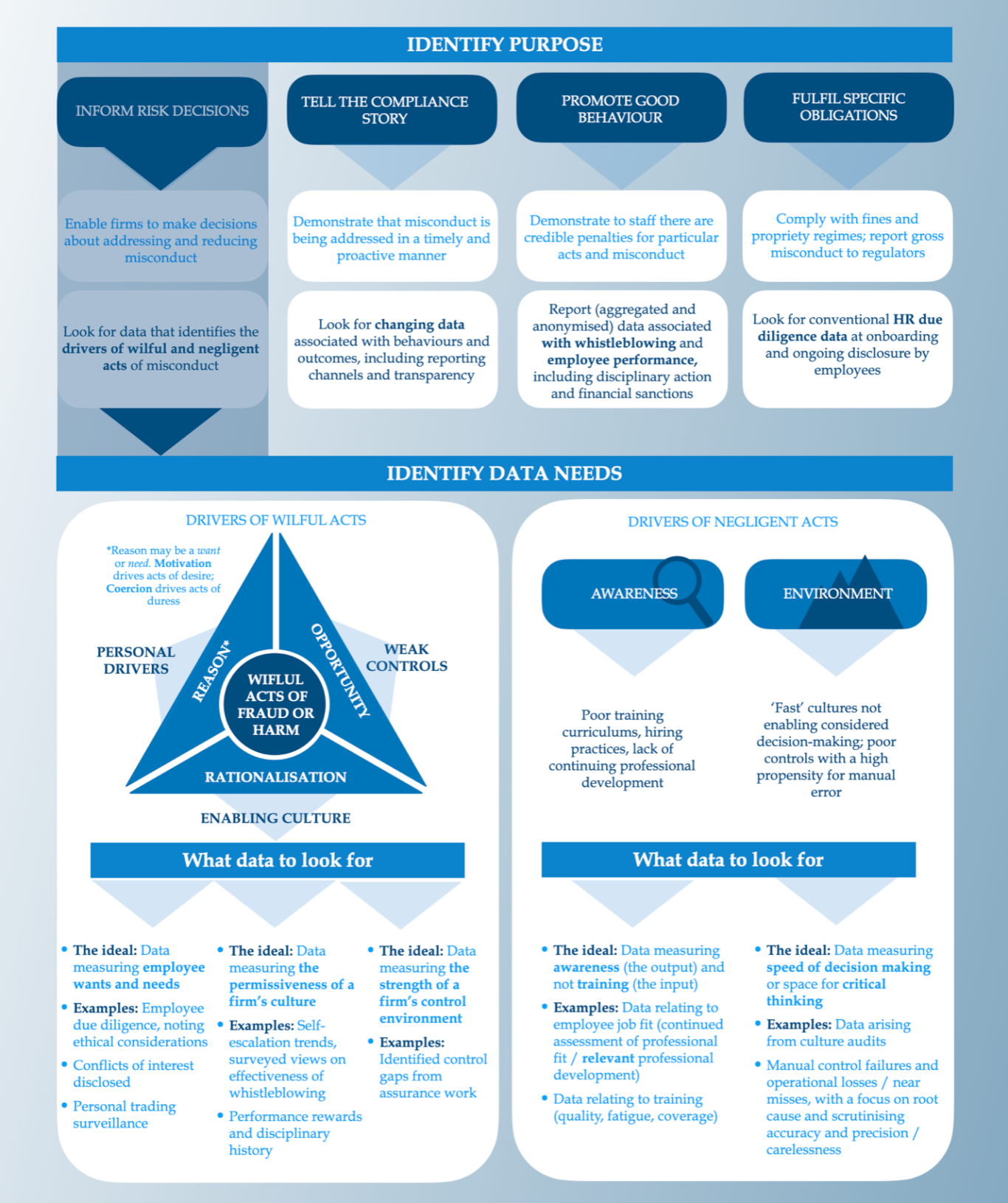

5. Purpose in practice: redesigning misconduct risk data

By putting the drivers of misconduct at the heart of data design, a firm can elevate its conduct risk management reporting. We illustrate this below.

Figure five: illustrating purpose in misconduct risk data design

6. Principles for avoiding compliance data fiction

7. The IC MasterClass Cheatsheet

The IC MasterClass Cheatsheet goes into further detail on how to deliver an elevated compliance data strategy that reduces the risk of data fiction. IC MasterClass can arrange curated sessions to help enhance your understanding of compliance data and how to enhance your compliance reporting: contact us today.

- Compliance data needs to serve a purpose: to inform risk decisions, tell the compliance story, promote good behaviour or fulfil a specific regulatory obligation

- Purpose is intrinsically linked to risk appetite, which in turn serves as a materiality threshold: whereby the omission or misstatement of the data could influence decision-making

- A good metric is clear and understandable, consistent and comparable, gives a faithful representation, and is verifiable

- Data fiction occurs when data is manipulated to mislead. Cherry picking data, focusing on low risk areas, presenting absolute numbers and removing context from reports are examples of this

- Without a commonly understood purpose, firms are likely to disrupt their strategies with data, rather than complement them

- Measuring the wrong data has a cost: administrative, technological, financial and reputational. It can also misdirect focus and undermine a firm’s risk management actions

- Compliance data arises wherever an activity has a compliance angle to it. Data owners will predominantly sit in front line teams. Clearly defining who owns data and who analyses it is integral to preventing duplicative or inconsistent metrics being produced

- Data can have a compliance ‘implication’ even if it is not created by an ‘act of compliance’

- Decentralised data processes, including reporting, will lead to duplication, inconsistent judgements, and opacity in assumptions and weightings

© Copyright Innovate Compliance Limited | All rights reserved | Reproduction or commercial use of any of the content on this site or other IC materials is prohibited without the express permission of Innovate Compliance

Innovate Compliance Limited is a UK registered company | number 15523445 | 63-66 Hatton Garden, Fifth Floor, Suite 23, London, England, EC1N 8LE

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.